As I mentioned previously, I was recently down in Gulf Shores for NCAA Beach Nationals. There’s a lot to learn from any championship event and this was no exception, so I want to dive right in. The unique format of NCAA Beach Volleyball means that each school puts up 5 pairs against each other and whichever school wins 3-out-of-5 pairs wins the duel. The best duels get tied 2-2 and come down to a 5th court that is almost always in a 3rd set.

At this year’s championship, there were 5 matches that fit that bill:

Cal v Long Beach 4s

Stanford v Grand Canyon 4s

LSU v FAU 4s

USC v TCU 5s

USC v UCLA 3s

I’ll fill in the links as I post each write-up.

For each match I’ll share some stats and highlight plays and I’ll connect in some more general coaching concepts.

Let’s turn to the Stanford v Grand Canyon matchup, which tied at 2-2 and came down to the 4s match of Stanford’s Vincent/Belardi v GCU’s Birch/Rowan.

The Stats

(From Stanford’s perspective, because they won the match)

Stanford Triangle Stats

+2 Total Point Differential

-3 Terminal Serves

+/- 0 First Ball

+5 Transition

Last week, we saw a match between Cal and Long Beach where Transition was a wash and First Ball was the deciding factor. In this match, Transition was the key for Stanford.

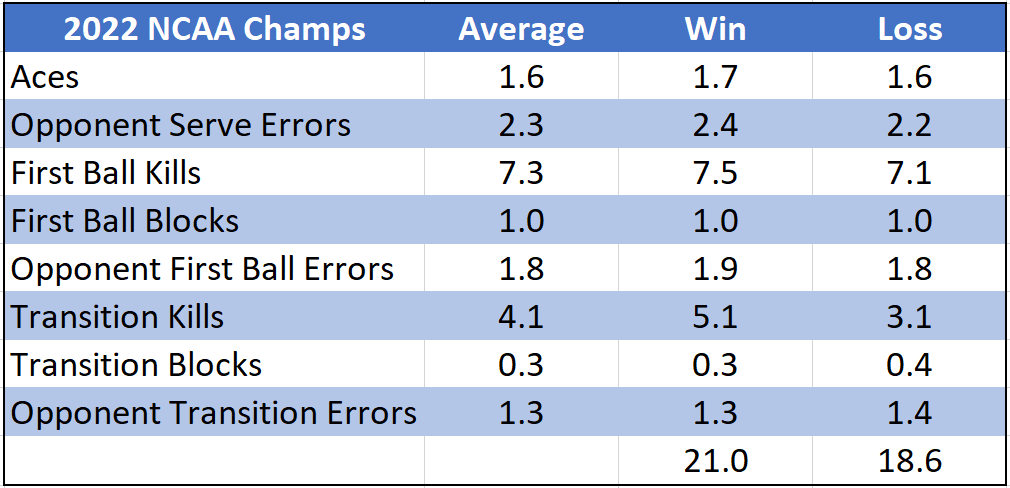

We’ve seen previously that Transition has been a determining factor in many NCAA Championship matches, with there being, on average, more of a difference between winning and losing teams in Transition than in First Ball.

Beach Week: NCAA Championship Triangles

This week is Beach Week at Smarter Volley. I dedicate the first three weeks of each month to indoor volleyball and the fourth week to the beach game. If you are purely here for indoor volleyball, you might want to skip this one. The theme of this current block of Beach Weeks is

Transition Stats

15 Stanford Transition Kills

3 Stanford Transition Stops

7 Grand Canyon Transition Kills

6 Grand Canyon Transition Stops

I’ll spare you the Shrek graphic, but again, here’s the value in peeling back some layers. In last week’s write-up, we saw Cal and Long Beach with the same amount of First Ball Kills, but it was Long Beach’s errors that did them in. This is the opposite, Stanford had 4 unforced errors in Transition compared to Grand Canyon with only 2. But Stanford was simply able to dig-to-kill more than Grand Canyon and, in a match that was decided by only 2 points, that was the difference.

The Principle: Dig-to-Kill

I’ve mentioned the Dig → Create → Convert chain before. I think this concept might be more important on the beach, because the digger is also usually the attacker. In indoor volleyball, few balls are set to the player who digs the ball. On-2 attacking is important on the beach, but most balls are still attacked by the digger.

So what does that mean?

You can’t just design your defense for digs and for the love of God please don’t design things around getting touches. Remember coaches: “nice touch,” means, “the other team just got the point.” We’re here to create transition opportunities we can kill, not to delay the ball from hitting the sand.

It also means that you should minimize the amount of training time where the ball is only dug (and not transitioned). You must must train digging as the start of a transition attack, not the end of a defensive effort. I had an email exchange a few months ago with a SmarterVolley reader who was coaching a high school beach program1. These are pretty good high school kids, definitely not beginners. I watched some video and one of the main pieces of feedback I had was to emphasize the ability to close the distance and get to the net when digging (or even receiving deep in the court).

Here’s the kind of play that makes an elite player like Nuss so special:

Digging deep to her left and then closing the distance with her legs underneath her. She even has enough power to step-out to a slightly miss-set ball and get enough pace to Beat The Puller.

Just asking your players to do this won’t make it happen overnight. There’s a lot of athleticism required to generate the power in the sand to take long approaches and then get vertical. But emphasizing it consistently in practice will help players improve. And from there, who knows how good they can get.

Awesome that beach volleyball is a high school sport in a lot of areas!