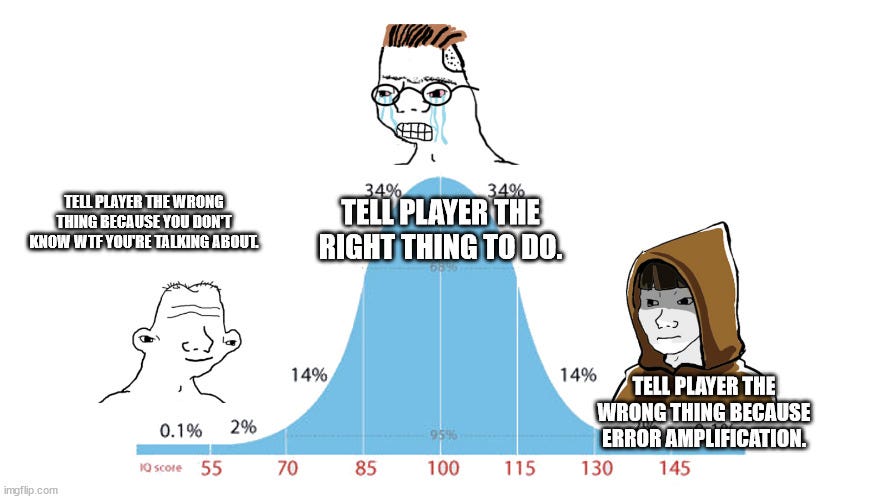

Error Amplification

Why do it right when you can do it wronger?

Last week we started diving into Rob Gray’s book, How We Learn To Move.

We talked about the idea of self-organization within boundaries. Define the result of the play (the intention) in clear terms, define the boundaries, and give the players some chances to find the right timing and touch within those boundaries.

Let’s look at another technique that relates to the self-organization principle, this time it’s error amplification. To quote directly from the book:

This type of constraints manipulation is sometimes called the Method of Amplification of Errors because it is taking a slight “flaw” in a movement pattern and making it much larger and louder to the perceptual system of the performer.

Another example can be seen in the study of golfers by Milanese and colleagues. Using a motion capture system, the researchers identified a particular error in the golf swing of 34 participants: not shifting their weight away from the ball onto their back foot while swinging. This is problematic because weight transfer serves to generate force and consequently distance on the shot. The golfers were then split into two training groups. The correctiveinstruction group were given the traditional type of coaching one would expect, specifically they were told to “Shift your body weight toward the BACK FOOT as far as possible while swinging”. In other words, they were told the solution to the problem.

The error amplification group were given a very odd instruction: “Shift your body weight toward the FRONT FOOT as far as possible while swinging”. So, in other words, they were told to make the problem even worse.

What was found? For the error amplification group, both club head and ball speed increased after training (what we would expect if weight is being transferred more effectively from the front to the back foot) while there was no significant improvement for either the direct instruction or a control group that received no training. So, counterintuitively, adding a constraint that exaggerates or amplifies a problem in a movement solution rather than trying to give the athlete the solution to correct it seems to be more effective.

Other commonly used examples of this type of training involve using a task constraint manipulation by changing equipment. For example, using a flexible shaft golf club or a PVC pipe instead of a baseball bat can serve to amplifying any “hitches” (i.e., unsmooth transfers of force) in a golfers or baseball player’s swing.

Counterintuitive indeed.

We can see how this relates to Goldilocks Method. Goldilocks is basically double-sided Error Amplification.

In 2017 I was coaching at University of Georgia in the spring. Nice time, nice group of kids, eager to learn and get better. It was a fun spring to coach. I can remember one particular player who could not stopping bobbing her arms as she passed. If you can visualize this: sometimes players join their hands a bit too high (say, in front of the belly button) and then they have to drop their hands down under the line of the serve, and then raise their arms back up to contact the ball. This is a complicated passing motion that will cause errors from time to time.

Every practice I’m working with passers.

“Come on [player], straight and simple.”

“Connect low and lift.”

“Low to high when we pass, not high-low-high”

“FOR THE LOVE OF GOD STOP BOBBING!!!”

Shockingly, the last one didn’t seem to help.

What was interesting about this was that she really couldn’t feel it very well. “Did I bob on that one?” was a common question after she passed. She would rarely definitely turn and say, “ok yeah, I totally felt that.” She could see it on video, she understood what we were talking about, but her body didn’t feel the movement very well.

And we’ve all had that. If anybody here is coaching younger players, you see it all the time. You demonstrate a 4-step approach and they take 3 and turn to you eagerly, awaiting your evaluation. You demo a 4-step approach and they take 17 steps and turn to you eagerly, awaiting your evaluation. Higher-level players rarely experience this level of disconnect, but all athletes experience degrees of this.

So one day I tried the following:

Joe: “Okay [player] I want you to INTENTIONALLY bob your arms when you pass this next ball.”

Player: (looks puzzled but does so)

Joe: “Okay, now pass with a simple lift.”

Player: (does)

Joe: “Okay now intentionally bob… okay now pass with a simple lift.”

Player: (proceeds to become an All-American)

The last statement is untrue but it did seem to help!

One thing that’s interesting is that her intentional bobs were often less-bobby than some of her normal passes, especially at first. Just gaining some feel for her arms instantly made it feel weird to have to bob them like that. And as she gained proficiency in this movement, her intentional bobs got bigger, but her simple lifts got simpler.

A definition of skill proficiency might be, how much variability in movement can you use and still produce the same result? You can see this with serving, for example. Take somebody who has a good feel for hitting a float serve and they can standing float, jump float, 2-hand jump float, standing beach jump float, spin the ball up in the air and make a float contact, etc, etc.

In contrast, I see often with poor servers that they have THEIR SERVE that they have to hit and God forbid if the conditions aren’t quite right. They can only serve from one part of the baseline to one area of the court with one specific approach type and one specific toss and only on a full moon with a certain air pressure in the ball.

This concept also makes me think of setting. In the workshop with Carli Lloyd and Alisha Glass, Carli talked about doing various drills where she had to make an outside set with power in some difficult situations. Young setters rely a lot on legs to push the ball to the outside, but some of Carli’s youth coaches had her setting the ball in situations where she couldn’t use her legs- such as standing flat-footed or even sitting in a chair.

At the risk of getting smacked down by the ghost of Carl McGown, I think there’s something to it. The easiest example there is jump setting. You can work with kids on having a faster release all you want, but as long as they can stand on the floor, absorb, and push off their legs, it can be hard to consciously speed up the release. But once you start jump setting? Good luck holding on to the ball while you’re only in the air for a half-second1. Either their release will change or they won’t be able to jump set.

Amplifying Errors In Practice

The good thing about this technique is that you don’t even need quite as much structure as Goldilocks. Any drill where a player is going to get multiple reps of the same skill within a fairly short time period will work. For example, a simple Split-Court Hitting or Doubles setup will work well.

“Okay, next ball I want you to get your second step well in front of the 10’ line when you hit… Okay, on this ball, let’s try to get toes to the 10’ line.”

“Okay, next ball, hit this ball with no double-arm lift…. Okay this ball, get a full double-arm lift2.”

And so on.

If you have a setup where a player gets multiple rounds at a skill, you can even have them do an error-amplified round, and then a regular round. Have a player do a whole passing round where they have to bob their arms. Then go back to normal for the next round. In theory, I would see this having a more powerful effect than the alternation, but it can be more difficult to implement into practice.

Alright, there we go, Error Amplification. Now go forth and tell your players to mess things up a bit.

It’s actually a reason why it’s not bad to have even young setters, who don’t really need to jump set, do some jump set practice. It can help develop the release.

I’m actually going to say “rubber bands” BecauseWinkleman but for ease of description in this article I left it as double-arm lift.