We’re approaching the end of this spring cross-training grab bag series. At the end of April I’ll put together a compilation of each of the Tuesday Toolbox, Friday Fitness, and Sandy Sundays series.

This Friday Fitness series has been focusing on what might be termed Strength and Conditioning for volleyball, only I contend that strength as traditionally expressed in long-duration barbell/dumbbell lifts isn’t very important and neither is conditioning.1 The SmarterVolley audience ranges from beginner coaches to high-level club to NCAA coaches to FIVB and pro level coaches. Everybody is in a bit of a different standpoint, so I’m picking and choosing some different topics, rather than a detailed top-to-bottom protocol.

I’m also trying to bias toward stuff that’s idiot teenager-proof, because I do think the heavy barbell stuff can have its uses if properly programmed, but it (a) requires additional facility time and space and (b) a level of teaching and supervision that is outside the scope of a typical volleyball coach. My ideal volleyball training session would see the S&C coach (if the program has one) come to the volleyball gym and assist with training, rather than the coach sending the players to the weight room.

I enjoy watching HS Track HoF coach Tony Holler’s “X-Factor” workouts:

What I like is that these are all drills that can be done by high school athletes in a large group, without intense supervision. That sort of sounds like stuff that might fit into my Itsy-Bitsy framework.

Everything in the above-video, with the exception of the bleacher plyos, is self-scaling, meaning it’s about as difficult as the athlete makes it. More explosive athletes will make the dynamic lunges faster and more explosive and less powerful athletes will do them slower. Great. And the bleacher plyo stuff is easy enough to scale as well; most teenage volleyball players will be able to do the 2-foot variations, and you just don’t progress to any of the 1-foot stuff until they are good at the 2-foot stuff. And the reality is that the average high school female athlete will never progress to something like the tall 1-foot bounces unless they are doing this stuff year-round. Even the vast majority of P5 women’s hitters won’t be close to doing that drill proficiently because of their size.

Or, to link back to the beginning of the post, because of their lack of strength as it applies to dynamic settings.

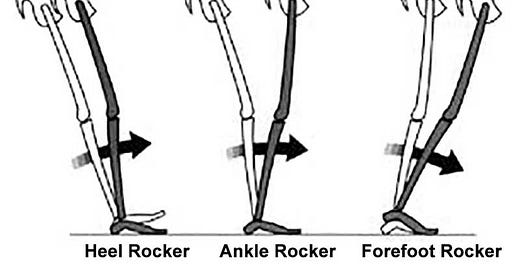

In the discussion of approach backswing mechanics, I mentioned the downside that many barbell lifts have on the shoulder. But barbell lifts like squatting and deadlifting are also detrimental to your feet. Or more specifically: you build power in the legs and hips without the corresponding ability to transfer that power through your feet.

There are clearly plenty of players who have built the ability to run fast and jump high while using barbell lifts. And plenty of S&C coaches who have utilized power lifts or olympic lifts to to help players to become more powerful in their sport. So what gives?

The success stories I see in those scenarios are usually either (a) coaches who used those methods in conjuction with other drills to build the feet/ankles or (b) coaches who used those methods on athletes who were already naturally springy in the feet and ankles. (B) is much more common than (A). But there have to be some things we can do to help athletes who aren’t naturally springy and who are, instead, a bit “heavy-footed.”

Here’s what I like instead:

Sled Push/Pull

We discussed this in a previous article, so check that out for more detail. The main point to emphasize is that pushing/pulling resistance requires the force to transfer through the feet, specifically the ball of the feet and the big toe, in a way that isn’t required in the barbell lifts. In fact, you will probably hear your strength coach saying, “sit back, push through the heels.” This is the opposite of what we want.

Jump Rope

Simple and old school, but jumping rope is a great foundational exercise for building some bounce. Also: it’s amazing how many teenage athletes are really bad at jumping rope. The coordination part isn’t a big deal because skills are specific, but if you have athletes who really struggle (after a session or two) to maintain an easy, bouncy flow when jumping rope, it’s likely an indication that they struggle to not just contract but also relax in movements. Relaxation = speed.

You don’t want to turn this into an intense conditioning drill. Athletes should aim to relax and maintain an easy, bouncy rhythm while breathing through the nose.

Spring Ankle

Cal Dietz of Minnesota has a great video series on this concept of Spring Ankle.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Smarter Volley by Joe Trinsey to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.