Transition Data Dump

I like numbers. Not everybody does. If you don’t like numbers, this might not be the post (or Substack) for you. Most NCAA numbers are courtesy of Volleymetrics, but some are from my own research. Also, if you want to learn how to dive deeper into the numbers, check out the DV4 Manual that Jeff Liu and I put together.

March has been Transition month. We looked at Transition Strength profiles:

We also looked at Transition Weakness profiles.

Let’s mine the numbers a little more and see what else pops up:

Transition Efficiency

Just straight-up Transition Attacking Efficiency is a pretty good measure of winning. 0.84 correlation with Transition Win % and 0.77 efficiency with Win % as a whole.1

The least-successful team here was Stanford, and they still won nearly 2/3 of their matches. Quite a bit of the Sweet 16 is represented here. Also worth noting that you don’t need to be a Transition-dependent team to be good in trans. Kentucky, Texas, and Stanford are the only 3 of this group that were significantly better in Trans than other areas of the game.

Also: Kentucky, Texas, and Georgia Tech… damn! Let’s appreciate how good you have to be to attack at a 0.300 clip in transition in NCAA women’s volleyball!

Trans To FB Ratio

Most teams attack better in First Ball than in Transition, but some attack better in trans. Here were the teams with the highest ratio of Transition to First Ball attacking, meaning they hit relatively better in trans than other teams. The overall trend here is not good; correlation to winning of -0.3. It’s possible to still be a winning team (WSU was successful, and Kentucky and Purdue were 13th and 14th overall in this metric) with a high ratio here, but it’s not something I’d consciously develop.

Just for fun, here’s the bottom-10 in this measure.

These were the 10 teams who were relatively the best First Ball attacking teams. Again, there’s variance among both the top and the bottom of this list, but the teams who are first ball-reliant tended to be a bit stronger.

The number of standout middles on the teams in the second group stands out to me. Pitt, Nebraska, Penn State, Wisconsin, and Florida all had All-American middles, while Washington State was the sole team with an All-American middle in the top group. As I talk about here, if you’re lagging in First Ball, it’s worth dialing in your middle attack a bit more.

And next let’s turn our attention to the defensive side of the ball.

Opponent Transition Efficiency

Pretty strong group of teams here, especially when you consider that #s 11, 12, and 13 are Purdue, Pitt, and Wisconsin.

The correlation between transition defense and winning was nearly the same as the correlation between transition offense and winning. Good teams are good at lots of things. There were transition-reliant teams here, but also a team like Nebraska, who was just a very good defensive team, regardless of whether the opponent was attacking in FB or Trans.

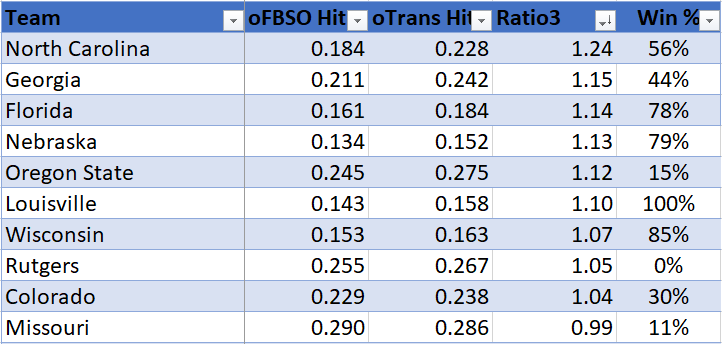

Trans to FB Defense Ratio

This is more of a curiosity stat, since it had a zero correlation to winning.2 But here’s the 10 teams that were relatively the best at defending in transition.

And here’s the flip side of that metric:

Rutgers, I can’t figure you out! You were relatively good at hitting in transition, but relatively bad at defending it! I wondered if there was a correlation between these two ratios (ie, teams that were relatively good at hitting in first ball would be relatively good at defending in first ball and vice versa), perhaps connected to how they train (this team practices a lot of first ball reps, this other team does a lot of transition drills) or something like that but… no. No correlation. How (relatively) good your hitters were in one phase didn’t correlate to how (relatively) good your defenders were in that phase.

Still, it’s always a fun metric that can place Rutgers in the same top-10 chart as Nebraska, Louisville, and Wisconsin!

A couple final curiosities

Good Zeroes

Okay we’re getting a little obscure here, but that’s what a data dump post is for, right?

This ratio is “good zeroes to bad zeroes,” or more specifically, “how often, when you get dug, do you get an easy ball back?” This also includes balls recycled off the block. Do you get a swing first? Or does the other team.

We see here that, in the Power 5 Women’s NCAA, getting an easy ball back over 1/4th of the time is pretty good. Interesting that Georgia Tech, Pitt, Louisville, and NCAA top the list. What’s going on in the ACC!?

It stands out to me that Pitt, a highly successful team, is notably low (relative to other elite teams) in transition efficiency, but was pretty good on their zeroes. That’s a way to out-perform slightly lower efficiency. Wisconsin, to a lesser extent in both directions, also fits that bill.

All of this stuff is correlated with each other. Good zeroes are correlated with efficiency- hit more scoring shots and you get more balls that are barely dug. Good zeroes are correlated with Trans Win % and overall Win % as well, at about the 0.4 level. Not the same as hitting efficiency, but not that far off something like Good Pass %.

Given that, on any team I’ve ever coached, passing accuracy is coached and valued much more than making good zeroes, there could be some easier marginal gains here.

Defensive Control

Okay here’s the defensive version of that last one. “How often does the other team make a good zero against you?” So it’s a lot about dig quality, but some about blocking too, since a ball recycled off your block counts as a good zero for the opponent.

Not quite as much correlation to winning as the offensive measure (about 0.25 compared to 0.45), but some successful teams near the top of this chart.

And the overall range here is similar on both the defensive and offensive ends: the best Defensive Control teams gave up a good zero about 1-out-of-5 times, while the worst gave one up about 1-out-of-3 times. The best Good Zero offensive teams got a good zero about 1-out-of-3 times, while the worst were around 1-out-of-5.

I’d be curious to see what it’s like at the high school level. At one hand the attacking is much less powerful, and balls are dug at a higher rate in high school. On the flip side, transition setting is much worse, and that influences how this stat gets kept. I briefly checked on the men’s Olympic side, and the numbers for France and Russia (the two teams in the men’s Olympic final) were both in the high-20s, so we’re looking at similar numbers on the elite men’s side as well.

Have any of you used a similar metric? Drop me a comment and let me know!

Clearly there’s other also-correlating factors at play here…

Remember that doesn’t mean it’s good or bad. It just means that this number being either high or low tells you no information about winning or losing.